5 No Estimates Decision-Making Strategies

One of the questions that I and other #NoEstimates proponents hear quite often is: How can we make decisions on what projects we should do next, without considering the estimated time it takes to deliver a set of functionality?

Although this is a valid question, I know there are many alternatives to the assumptions implicit in this question. These alternatives - which I cover in this post - have the side benefit of helping us focus on the most important work to achieve our business goals.

Below I list 5 different decision-making strategies (aka decision making models) that can be applied to our software projects without requiring a long winded, and error prone, estimation process up front.

What do you mean by decision-making strategy?

A decision-making strategy is a model, or an approach that helps you make allocation decisions (where to put more effort, or spend more time and/or money). However I would add one more characteristic: a decision-making strategy that helps you chose which software project to start must help you achieve business goals that you define for your business. More specifically, a decision-making strategy is an approach to making decisions that follows your existing business strategy.

Some possible goals for business strategies might be:

- Growth: growing the number of customer or users, growing revenues, growing the number of markets served, etc.

- Market segment focus/entry: entering a new market or increasing your market share in an existing market segment.

- Profitability: improving or maintaining profitability.

- Diversification: creating new revenue streams, entering new markets, adding products to the portfolio, etc.

Other types of business goals are possible, and it is also possible to mix several goals in one business strategy.

Different decision-making strategies should be considered for different business goals. The 5 different decision-making strategies listed below include examples of business goals they could help you achieve. But before going further, we must consider one key aspect of decision making: Risk Management.

The two questions that I will consider when defining a decision-making strategy are:

- 1. How well does this decision proposal help us reach our business goals?

- 2. Does the risk profile resulting from this decision fit our acceptable risk profile?

Are you taking into account the risks inherent in the decisions made with those frameworks?

All decisions have inherent risks, and we must consider risks before elaborating on the different possible decision-making strategies. If you decide to invest in a new and shiny technology for your product, how will that affect your risk profile?

A different risk profile requires different decisions

Each decision we make has an impact on the following risk dimensions:

- Failing to meet the market needs (the risk of what).

- Increasing your technical risks (the risk of how).

- Contracting or committing to work which you are not able to staff or assign the necessary skills (the risk of who).

- Deviating from the business goals and strategy of your organization (the risk of why).

The categorization above is not the only possible. However it is very practical, and maps well to decisions regarding which projects to invest in.

There may good reasons to accept increasing your risk exposure in one or more of these categories. This is true if increasing that exposure does not go beyond your acceptable risk profile. For example, you may accept a larger exposure to technical risks (the risk of how), if you believe that the project has a very low risk of missing market needs (the risk of what).

An example would be migrating an existing product to a new technology: you understand the market (the product has been meeting market needs), but you will take a risk with the technology with the aim to meet some other business need.

Aligning decisions with business goals: decision-making strategies

When making decisions regarding what project or work to undertake, we must consider the implications of that work in our business or strategic goals, therefore we must decide on the right decision-making strategy for our company at any time.

Decision-making Strategy 1: Do the most important strategic work first

If you are starting to implement a new strategy, you should allocate enough teams, and resources to the work that helps you validate and fine tune the selected strategy. This might take the form of prioritizing work that helps you enter a new segment, or find a more valuable niche in your current segment, etc. The focus in this decision-making approach is: validating the new strategy. Note that the goal is not "implement new strategy", but rather "validate new strategy". The difference is fundamental: when trying to validate a strategy you will want to create short-term experiments that are designed to validate your decision, instead of planning and executing a large project from start to end. The best way to run your strategy validation work is to the short-term experiments and re-prioritize your backlog of experiments based on the results of each experiment.

Decision-making Strategy 2: Do the highest technical risk work first

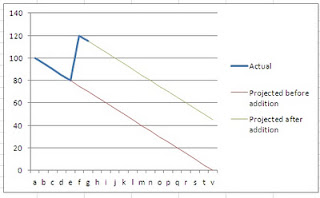

When you want to transition to a new architecture or adopt a new technology, you may want to start by doing the work that validates that technical decision. For example, if you are adopting a new technology to help you increase scalability of your platform, you can start by implementing the bottleneck functionality of your platform with the new technology. Then test if the gains in scalability are in line with your needs and/or expectations. Once you prove that the new technology fulfills your scalability needs, you should start to migrate all functionality to the new technology step by step in order of importance. This should be done using short-term implementation cycles that you can easily validate by releasing or testing the new implementation.

Decision-making Strategy 3: Do the easiest work first

Suppose you just expanded your team and want to make sure they get to know each other and learn to work together. This may be due to a strategic decision to start a new site in a new location. Selecting the easiest work first will give the new teams an opportunity to get to know each other, establish the processes they need to be effective, but still deliver concrete, valuable working software in a safe way.

Decision-making Strategy 4: Do the legal requirements first

In medical software there are regulations that must be met. Those regulations affect certain parts of the work/architecture. By delivering those parts first you can start the legal certification for your product before the product is fully implemented, and later - if needed - certify the changes you may still need to make to the original implementation. This allows you to improve significantly the time-to-market for your product. A medical organization that successfully adopted agile, used this project decision-making strategy with a considerable business advantage as they were able to start selling their product many months ahead of the scheduled release. They were able to go to market earlier because they successfully isolated and completed the work necessary to certify the key functionality of their product. Rather then trying to predict how long the whole project would take, they implemented the key legal requirements first, then started to collect feedback about the product from the market - gaining a significant advantage over their direct competitors.

Decision-making Strategy 5: Liability driven investment model

This approach is borrowed from a stock exchange investment strategy that aims to tackle a problem similar to what every bootstrapped business faces: what work should we do now, so that we can fund the business in the near future? In this approach we make decisions with the aim of generating the cash flows needed to fund future liabilities.

These are just 5 possible investment or decision-making strategies that can help you make project decisions, or even business decisions, without having to invest in estimation upfront.

None of these decision-making strategies guarantees success, but then again nothing does except hard work, perseverance and safe experiments!

In the upcoming workshops (Helsinki on Oct 23rd, Stockholm on Oct 30th) that me and Woody Zuill are hosting, we will discuss these and other decision-making strategies that you can take and start applying immediately. We will also discuss how these decision making models are applicable in day to day decisions as much as strategic decisions.

If you want to know more about what we will cover in our world-premiere #NoEstimates workshops don't hesitate to get in touch!

Your ideas about decision-making strategies that do not require estimation

You may have used other decision-making strategies that are not covered here. Please share your stories and experiences below so that we can start collecting ideas on how to make good decisions without the need to invest time and money into a wasteful process like estimation.

Labels: #NoEstimates, agile, agile estimation, decision making, decision making frameworks, decisions, lean, lean thinking, management, portfolio management, project management, risk management, risk strategy

RSS link